Modular Error Reporting with Dependent Lenses

A big part of programming language design is in feedback delivery. One aspect of feedback is parse errors. Parsing is a very large area of research and there are new developments from industry that make it easier and faster than ever to parse files. This post is about an application of dependent lenses that facilitate the job of reporting error location from a parsing pipeline.

What is parsing & error reporting

A simple parser could be seen as a function with the signature

parse : String -> Maybe output

where output is a parsed value.

In that context, an error is represented with a value of Nothing, and a successful value is represented with Just. However, in the error case, we don’t have enough information to create a helpful diagnostic, we can only say “parse failed” but we cannot say why or where the error came from. One way to help with that is to make the type aware of its context and carry the error location in the type:

parseLoc : string -> Either Loc output

where Loc holds the file, line, and column of the state of the parser.

This is a very successful implementation of a parser with locations and many languages deployed today use a similar architecture where the parser, and its error-reporting mechanism, keep track of the context in which they are parsing files and use it to produce helpful diagnostics.

I believe that there is a better way, one that does not require a tight integration between the error-generating process (here parsing) and the error-reporting process (here, location tracking). For this, I will be using container morphisms, or dependent lenses, to represent parsing and error reporting.

Dependent lenses

Dependent lenses are a generalisation of lenses where the backward part makes use of dependent types to keep track of the origin and destination of arguments. For reference the type of a lens Lens a a' b b' is given by the two functions:

get : a -> bset : a -> b' -> a'

Dependent lenses follow the same pattern, but their types are indexed:

record DLens : (a : Type) -> (a' : a -> Type) -> (b : Type) -> (b' : b -> Type) where

get : a -> b

set : (x : a) -> b' (get x) -> a' x

The biggest difference with lenses is the second argument of set: b' (get x). It means that we always get a b' that is indexed over the result of get, for this to typecheck, we must know the result of get.

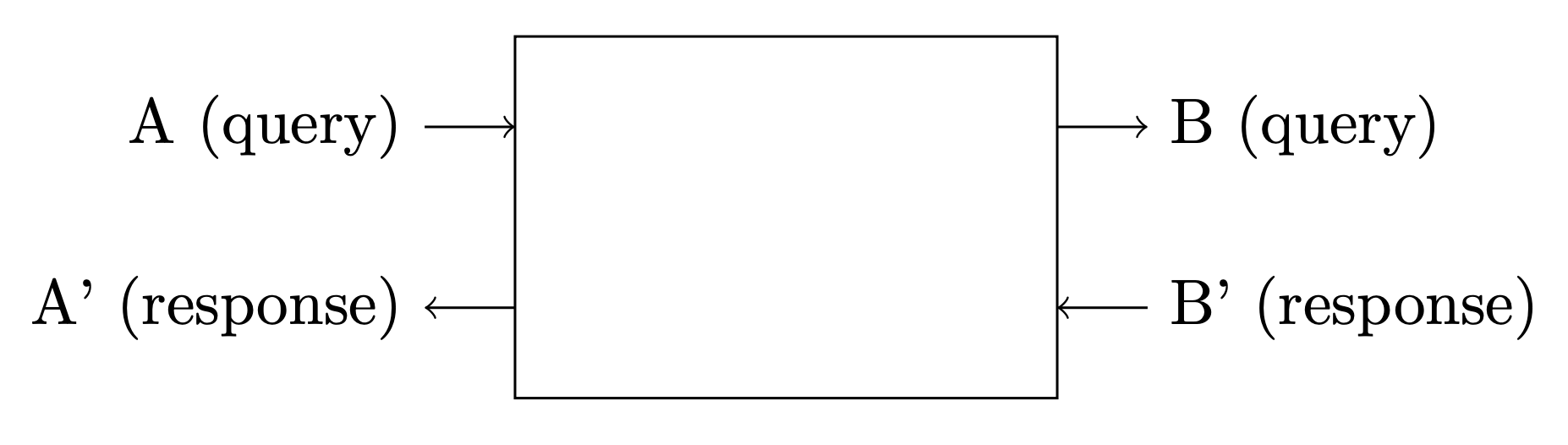

This change in types allows a change in perspective. Instead of treating lenses as ways to convert between data types, we use lenses to convert between query/response APIs.

On each side A and B are queries and A' and B' are corresponding responses. The two functions defining the lens have type get : A -> B, and set : (x : A) -> A' (get x) -> B' x, that is, a way to convert queries together, and a way to rebuild responses given a query. A lens is therefore a mechanism to map between one API to another.

If the goal is to find on what line an error occurs, then what the get function can do is split our string into multiple lines, each of which will be parsed separately.

splitLines : String -> List String

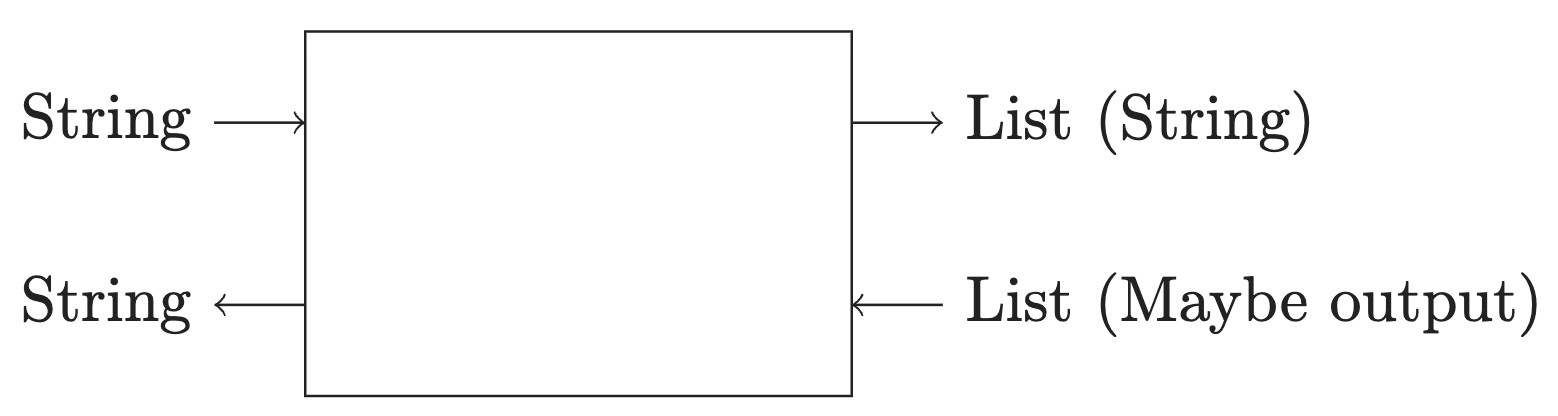

Once we have a list of strings, we can call a parser on each line, this will be a function like above parseLine : String -> Maybe output. By composing those two functions we have the signature String -> List (Maybe output). This gives us a hint as to what the response for splitLine should be, it should be a list of potential outputs. If we draw our lens again we have the following types:

We are using (String, String) on the left to represent “files as inputs” and “messages as outputs” both of which are plain strings.

There is a slight problem with this, given a List (Maybe output) we actually have no way to know which of the values refer to which line. For example, if the outputs are numbers and we know the input is the file

23

24

3

and we are given the output [Nothing, Nothing, Just 3] we have no clue how to interpret the Nothing and how it’s related to the result of splitting the lines, they’re not even the same size. We can “guess” some behaviors but that’s really flimsy reasoning, ideally the API translation system should keep track of that so that we don’t have to guess what’s the correct behavior. And really, it should be telling us what the relationship is, we shouldn’t even be thinking about this.

So instead of using plain lists, we are going to keep the information in the type by using dependent types. The following type keeps track of an “origin” list and its constructors store values that fulfill a predicate in the origin list along with their position in the list:

data Some : (a -> Type) -> List a -> Type where

None : Some p xs

This : p x -> Some p xs -> Some p (x :: xs)

Skip : Some p xs -> Some p (x :: xs)

We can now write the above situation with the type Some (const Unit) ["23", "", "24", "3"] which is inhabited by the value Skip $ Skip $ Skip $ This () None to represent the fact that only the last element is relevant to us. This ensures that the response always matches the query.

Once we are given a value like the above we can convert our response into a string that says "only 3 parsed correctly".

A Simple parser

Equipped with dependent lenses, and a type to keep track of partial errors, we can start writing a parsing pipeline that keeps track of locations without interfering with the actual parsing. For this, we start with a simple parsing function:

containsEven : String -> Maybe Int

containsEven str = parseInteger str >>= (\i : Int => toMaybe (even i) i)

This will return a number if it’s even, otherwise it will fail. From this we want to write a parser that will parse an entire file, and return errors where the file does not parse. We do this by writing a lens that will split a file into lines and then rebuild responses into a string such that the string contains the line number.

splitFile : (String :- String) =%> SomeC (String :- output)

splitFile = MkMorphism lines printErrors

where

printError : (orig : List String) -> (i : Fin (length orig)) -> String

printError orig i = "At line \{show (cast {to = Nat} i)}: Could not parse \"\{index' orig i}\""

printErrors : (input : String) -> Some (const error) (lines input) -> String

printErrors input x = unlines (map (printError (lines input)) (getMissing x))

Some notation: =%> is the binary operator for dependent lenses, and :- is the binary operator for non-dependent boundaries. Later !> will be used for dependent boundaries.

printErrors builds an error message by collecting the line number that failed. We use the missing values from Some as failed parses. Equipped with this program, we should be able to generate an error message that looks like this:

At line 3: could not parse "test"

At line 10: could not parse "-0.012"

At line 12: could not parse ""

The only thing left is to put together the parser and the line splitter. We do this by composing them into a larger lens via lens composition and then extracting the procedure from the larger lens. First we need to convert our parser into a lens.

Any function a -> b can also be written as a -> () -> b and any function of that type can be embedded in a lens (a :- b) =%> (() :- ()). That’s what we do with our parser and we end up with this lens:

parserLens : (String :- Maybe Int) =%> CUnit -- this is the unit boundary () :- ()

parserLens = embed parser

We can lift any lens with a failable result into one that keeps track of the origin of the failure:

lineParser : SomeC (String :- Int) =%> CUnit

lineParser = someToAll |> AllListMap parserLens |> close

We can now compose this lens with the one above that adjusts the error message using the line number:

composedParser : (String :- String) =%> CUnit

composedParser = splitFile |> lineParser

Knowing that a function a -> b can be converted into a lens (a :- b) =%> CUnit we can do the opposite, we can convert any lens with a unit codomain into a simple function, which gives us a very simple String -> String program:

mainProgram : String -> String

mainProgram = extract composedParser

Which we can run as part of a command-line program

main : IO ()

main = do putStrLn "give me a file name"

fn <- getLine

Right fileContent <- readFile fn

| Left err => printLn err

let output = mainProgram fileContent

putStrLn output

main

And given the file:

0

2

-3

20

04

1.2

We see:

At line 2: Could not parse ""

At line 3: Could not parse "-3"

At line 6: Could not parse "1.2"

Handling multiple files

The program we’ve seen is great but it’s not super clear why we would bother with such a level of complexity if we just want to keep track of line numbers. That is why I will show now how to use the same approach to keep track of file origin without touching the existing program.

To achieve that, we need a lens that will take a list of files, and their content, and keep track of where errors emerged using the same infrastructure as above.

First, we define a filesystem as a mapping of file names to a file content:

Filename = String

Content = String

Filesystem = List (Filename * Content)

A lens that splits problems into files and rebuilds errors from them will have the following type:

handleFiles : Interpolation error =>

(Filesystem :- String) =%> SomeC (String :- error)

handleFiles = MkMorphism (map π2) matchErrors

where

matchErrors : (files : List (String * String)) ->

Some (const error) (map π2 files) ->

String

matchErrors files x = unlines (map (\(path && err) => "In file \{path}:\n\{err}") (zipWithPath files x))

This time I’m representing failures with the presence of a value in Some rather than its absence. The rest of the logic is similar: we reconstruct the data from the values we get back in the backward part and return a flat String as our error message.

Combining this lens with the previous parser is as easy as before:

filesystemParser : (Filesystem :- String) =%> CUnit

filesystemParser = handleFiles |> map splitFile |> join {a = String :- Int} |> lineParser

fsProgram : Filesystem -> String

fsProgram = extract filesystemParser

We can now write a new main function that will take a list of files and return the errors for each file:

main2 : IO ()

main2 = do files <- askList []

filesAndContent <- traverse (\fn => map (fn &&) <$> readFile fn) (reverse files)

let Right contents = sequence filesAndContent

| Left err => printLn err

let result = fsProgram contents

putStrLn result

We can now write two files. file1:

0

2

-3

20

04

1.2

file2:

7

77

8

And obtain the error message:

In file 'file1':

At line 2: Could not parse ""

At line 3: Could not parse "-3"

At line 6: Could not parse "1.2"

In file 'file2':

At line 0: Could not parse "7"

At line 1: Could not parse "77"

All that without touching our original parser, or our line tracking system.

Conclusion

We’ve only touched the surface of what dependent lenses can do for software engineering by providing a toy example. Yet, this example is simple enough to be introduced, and resolved in one post, but also shows a solution to a complex problem that is affecting parsers and compilers across the spectrum of programming languages. In truth, dependent lenses can do much more than what is presented here, they can deal with effects, non-deterministic systems, machine learning, and more. One of the biggest barriers to mainstream adoption is the availability of dependent types in programming languages. The above was written in idris, a language with dependent types, but if your language of choice adopts dependent types one day, then you should be able to write the same program as we did just now, but for large-scale production software.

The program is available on gitlab.