On Organization

Cross-posted from Oliver’s Substack blog, EconPatterns

Leonard Read wrote his 1958 essay, I, Pencil, to drive the point home in dramatic prose that even a contraption as humble as the eponymous writing utensil depends on a wide variety of raw materials, production processes, labor, and technological advancements, to come together — all coordinated by the marvel of the market system.

“Consider the millwork in San Leandro. The cedar logs are cut into small, pencil-length slats less than one-fourth of an inch in thickness. These are kiln dried and then tinted for the same reason women put rouge on their faces. People prefer that I look pretty, not a pallid white. The slats are waxed and kiln dried again. How many skills went into the making of the tint and the kilns, into supplying the heat, the light and power, the belts, motors, and all the other things a mill requires? Sweepers in the mill among my ancestors? Yes, and included are the men who poured the concrete for the dam of a Pacific Gas & Electric Company hydroplant which supplies the mill’s power!”

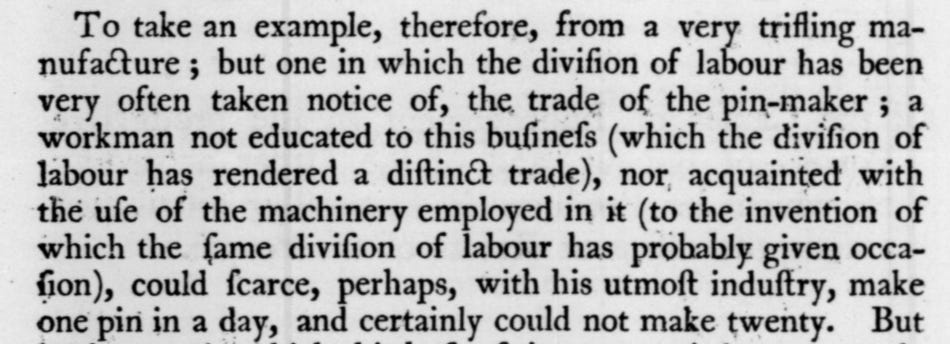

Milton Friedman made a truncated version of Read’s pencil story famous in a 1980 television special, and in the process connected it to another famous story from economic history about the production of a seemingly simple object: Adam Smith’s parable of the pin factory.

But one detail eluded Friedman: the step-by-step process of putting a pin together that opens Adam Smith’s magnum opus The Wealth of Nations to explain the division of labor, happens entirely under one roof. No handover across markets is mentioned until, presumably, the finished product is sold in bulk.

The same, we could surmise, might perfectly well hold true for Read’s story. There’s no reason why a pencil maker should not also mine the graphite needed for their one marketable product, harvest the rubber, or produce the electricity.

All of this has happened in the history of industrial production. But we can extrapolate from these stories and wonder if Smith’s pin maker also mills its raw material, iron or steel of a given quality, or if Read’s resource-conscious pencil maker would go as far as producing the mining machinery in-house, or maybe that’s the point where it’s willing to hand over the reigns to someone more qualified.

Organizations as tectonic plates

Abstracting away from these two stories, we can ask the question where in a complex production process should we put the handovers? The unremarkable-sounding name for this question is the make-or-buy decision, or, if a more academic term is needed, the degree of vertical (dis)integration. In operations, we speak of production depth.

Abstracting even further away, we can also ask where within any larger network of interactions, social or economic, should we draw the boundaries?

This question, on multiple layers, will occupy us quite a bit.

We can think of it popping up in the context of industrial production and market exchange: the economic sphere, in the context of public goods and livelihood risks: the political sphere, or even in the context of language, religion, and shared expressions of ideas and beliefs: the social sphere.

The laws by which we draw these boundaries, consciously or habitually, share some commonalities while there are also rules that hold only for one of these layers. Capturing them in design patterns is what this post is about.

For the economic sphere, which forms our primary concern, Oliver Williamson has established the fundamental dichotomy in the title of his first book: markets vs hierarchies, as shorthand for activities across firms vs activities within firms.

But in both governance mechanisms (to appropriate the title of Williamson’s final book), these labels hide some intricate machinery under the hood: “hierarchy” might be the canonical form of structuring interactions within, and “market” for interactions across organizations. But these terms contain a multitude of moving parts, all of which are subject to a myriad of design decisions.

Hierarchy is the canonical reporting structure for any larger organization. It’s ubiquitous enough that we can use the two terms synonymously, even if they’re not perfectly identical. It takes on the form of an upside-down tree (in the graph-theoretic sense), with its root node at the top.

The branches in a hierarchy describe vertical relationships, usually one-to-many, also known command-and-control. The superior defines tasks for the subordinates to undertake, provides the necessary resources, monitors, evaluates, and recompenses the work effort — at least in theory.

In theory hierarchy is a sorting mechanism by seniority, a catch-all term that encompasses more experience, more ability to put individual tasks in context and orchestrate them: more ability to manage. In practice, the lofty goal of sorting by superior skill is at best approximated but rarely reached.

In practice, hierarchies take many forms based on and sometimes even deviating from this fundamental design pattern. They can be steeper or flatter, they can incorporate matrix elements, they can be stiff or flexible.

“Reorganization” is a popular game played in the higher echelons of most corporate hierarchies and a neverending income stream for consultants, usually deeply unpopular among those manning the trenches.

This just shows that finding the perfect organizational structure is elusive for all but the simplest organizations.

Market is the catch-all term for all economic interactions that happen between organizations. But typically we think of a market more narrowly as a central place where many buyers meet many sellers: an agora.

In reality most economic interactions are of the few-to-few, few-to-one, or one-to-one variety, shaped by relational rather than market interaction. The key ingredient that the economic abstraction of a many-to-many market requires is the “coincidence of wants”: buyers and sellers wanting to trade the very same thing at a price they can both agree upon have to come together at the same place and the same time.

This is often tricky to achieve, and might require two steps mentioned in the first newsletter: displacement in space or time, transportation or storage, to bridge the gap between producer and consumer. Even the advent of online marketplaces did little to change this.

Beyond the recurring reorganizations typically triggered by underperformance, companies have also been known to first outsource their entire distribution network just to reverse course and bring it back in-house. So the make-or-buy label hides a non-trivial problem with massive costs but no obvious solution.

But other than the recognition that markets, organizations, and the boundary inbetween are subject to design choices which ostensibly influence performance, can we offer another explanation for how to split a supply network into its constituent parts other than the Coasean “costs of carrying out the exchange transactions in the open market”?

To reduce the work of half a dozen Nobelists including Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson to a tweet-length statement (which might itself evolve into a pattern), the make-or-buy decision boils down to the choice between cost and control.

Expressed in another way, more exactly expressed in accounting terms, the cost of holding control over the production process vs the cost of losing control over it.

This is the point where we can bring in the patterns from the first two newsletters. Assuming under Adam Smith’s division of labor that there is another producer who can produce our part cheaper than we could do it in-house, what are costs of losing control?

They are the costs of negative surprise.

While it’s in Read’s essay perfectly within the supplier’s self-interest to ship us the part in the volume ordered, there are two reasons why the shipment might stall: accidentally or deliberately.

Accidental production stops, or more exactly fluctuation between demand and supply that trigger stock-outs, are fairly common occurrences and the daily of supply bottleneck managers. The risk that a stock-out can trigger massive knock-on costs, the aforementioned missing five-dollar part that can stop a ten-million-dollars-per-hour production line and reduce finished products into 99.9%-finished unsellable inventory drive the decision to increase production depth even if there is no ill will by the supplier.

But the supplier knows this and can withhold deliveries strategically, essentially holding them hostage in order to negotiate better terms. The world of procurement is even in normal times rougher than portrayed by Read. Add an external shock to the supply infrastructure and planning cycles, inventory costs, and strategic maneuvering can explode.

Organizations as belief structures

But can we abstract away from the purely economic — most organizations are not in their intent economic — and express this avoidance of negative surprise as a design pattern for drawing the boundaries around organizations, or viewed from the other end: how to split a network of interactions, social, political, or economic, into coherent clusters which we might want to call organizations or, more specifically, companies, parties, states, religious communities?

In the world I’ve drawn so far, the need for design (and the need to capture them in design patterns) arises from the myriad of moving parts that require design choices on multiple levels: we have to choose between market and hierarchy, once we choose hierarchy we have to choose the structure of the hierarchy, including its governance structure, and another level down we have to decide on the shape of each reporting relationship, including who gets to sit on each end.

This is a world of high uncertainty and while we would like to resolve each design question empirically, empiricism is costly, so we will ultimately end up with goal conflict.

This goal conflict, which shapes the boundary of the organization, can be expressed in three patterns.

The first fundamental problem of organization is resolving the conflict between moving forward and staying together.

The second fundamental problem of organization is resolving the conflict between moving forward and staying put.

The third fundamental problem of organization is to decide which direction is forward.

All organizations have to resolve this goal conflict — literally “where do we go from here?” — or risk breaking up. Or expressed differently, the tectonic rifts between factions occur where these goal conflicts are unresolvable.

Using another pattern, the paradigm of traditional industrial organization introduced by Ed Chamberlin and applied by Joe Bain, “structure, conduct, performance” is a more general translation as “given the situation we’re in, of all the options available, which courses of action are the ones that promise the most success?”

Applying this paradigm requires coming to an agreement on a mapping between actions (conduct) and future outcomes (performance) given a set of starting conditions both internal and external (structure). This mapping requires expressing and ranking subjective expectations of conditional futures: beliefs (as opposed to objective probabilities in the statistical nomenclature). Where these beliefs diverge sufficiently, coordinating efforts within an organization is no longer feasible.

Competition is not only, as economic textbooks imply, competition between like products, but competition between differing courses of action based on differing beliefs about their feasibility.

This underlying idea, that boundaries emerge where coherence of beliefs breaks down between participants, will come up repeatedly in the future, and it is the main reason why organization rather than market exchange takes pride of place in this discussion — very simply because from a design perspective, market exchange is simply a special form of organization.