Stocks, Flows, Transformations: The Cybernetic Economy

Cross-posted from Oliver’s Substack blog, EconPatterns

On a certain level of abstraction, an economy can be described as a network of stocks, flows, and transformations. Let’s call this level the cybernetic economy.

Stocks, flows, transformations

Stocks and flows are two fundamental forms of displacement: in time and space respectively, and they are typically restricted by upper and lower capacity constraints: overstock vs stockout, overflow vs desiccation.

Transformation in the usual sense of industrial production means the recombination of inputs to produce new outputs, but we can also include creation and consumption as starting and endpoints of network flow. In the case of natural resources, creation often takes the form of extraction.

The stocks and flows usually come in the form of information, materials, effort, payments, equipment, and on a more abstract level, risks, beliefs, rights, and commitments. Risk is just as much an economic good that can be transformed, bundled, disassembled, transported as any physical material.

Most of these objects should sound familiar from economic textbooks, especially macroeconomic textbooks. The cybernetic economy differs from this textbook treatment mostly by explicitly highlighting the network of interactions, and by stressing the global ramifications of local interactions.

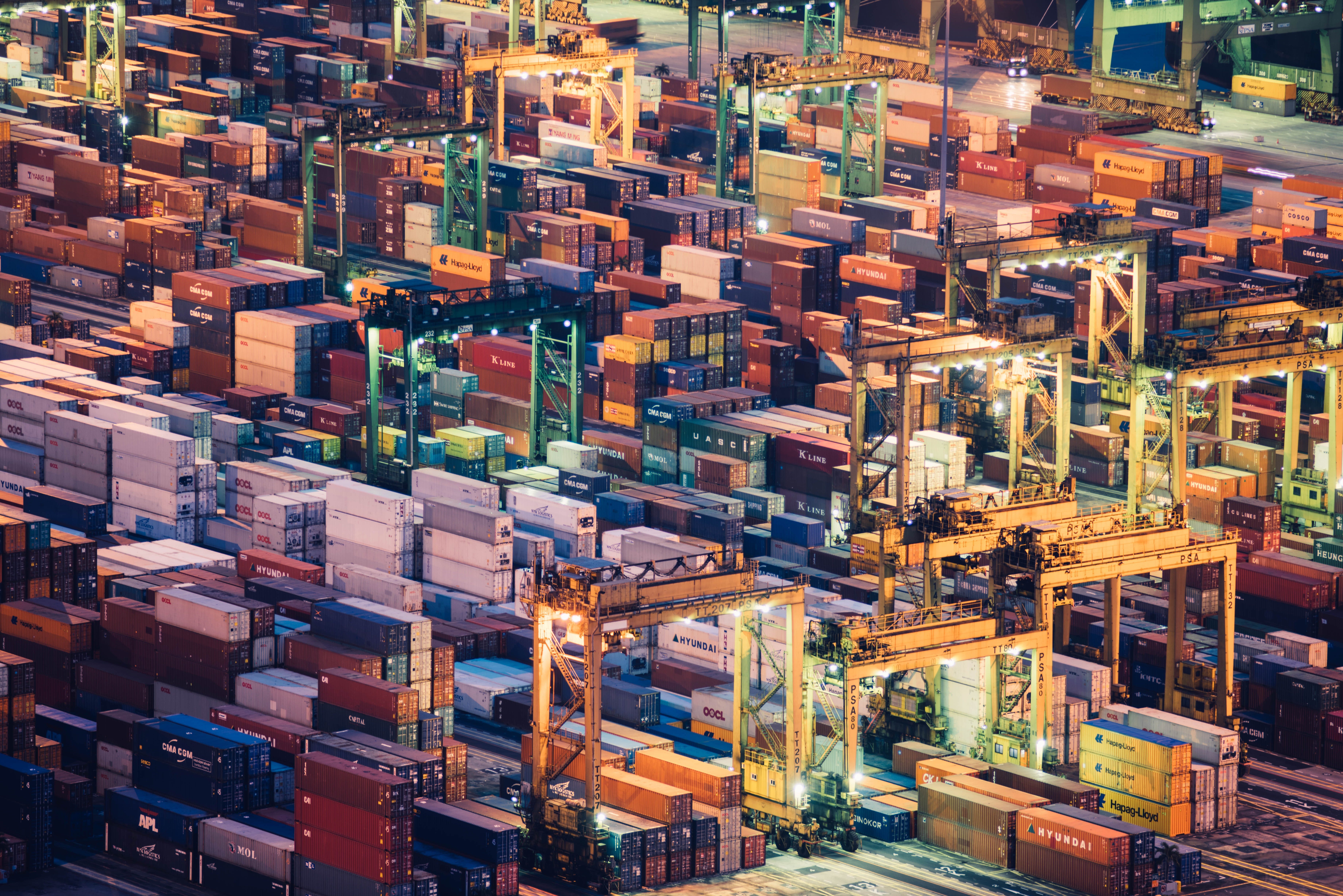

This network view of the economy on the other hand should be familiar to anyone with a background in industrial production, where orchestrating multi-step processes on shop floors densely packed with machines, pathways, buffers, and assembly stations is a major part of the job description, and where stockouts of five-dollar parts can stop ten-million-an-hour assembly lines — as can pathways congested by improvised material buffer overflows.

Economics, especially macroeconomics, usually skips this operational layer for the sake of expositional expediency, and for the most part it does ok doing so. As long as the operational friction stays within bounds, no stocks and flows pushing against their upper or lower capacity limits, no production schedules foiled by unobtainable five-dollar components, we can safely assume a frictionless world and focus on the established gears and levers central to macroeconomic inquiry.

In other words, as long as there is only a modicum of disorder in the economy, it’s perfectly fine to assume a well-ordered economy.

Which underlines a key principle: the right level of aggregation matters. A map is not the territory, but we might need different maps to do different things within the territory. In the same sense we can drop operational details and aggregate activity on a high level as long as we can be sure that the loss of realism — the loss of predictability — is inconsequential for the task at hand.

But we should have a more fine-grained map at the ready just in case our survey map fails to capture the finer points.

The cybernetic economy

The economy we’re looking at is an economy that can be disaggregated and disassembled to the individual component, the individual participant, the individual activity, just as needed whenever it is needed.

I’m resurrecting the somewhat outmoded term “cybernetic” for it because it conveys the focus on flows, on routing, buffering, concatenating, on orchestrating activities and resources.

Routing, network flow, buffering, job shop scheduling, machine replacement models are all standard tools of the trade in operations research. They are no longer, or not yet again, standard tools in economics, but in order to describe the economic activities as intended, and to couch them in a wider social and political context, they should become economic tools again.

EconPatterns intends to bring them back together under the same motivation that it intends to bring mathematical, statistical and computational tools together: to build up a toolset which we can use to design economic objects.

But, and this is the conjurer’s trick, it’ll do so almost entirely without resorting to formal modeling or even mathematical notation. This is not out of nostalgia for an era where political economy was a branch of the philosophical faculties. The economy is as data rich as any field of inquiry and we seem to have just enough recognizable, repeating and generalizable patterns to give the scientific method a try.

But the point of the exercise is to develop an economic design language, to establish a conceptual foundation, rather to rephrase current economic knowledge. This is why it invokes the famous Bauhaus Vorkurs, the foundational course that gave the Bauhaus students a starting point from which to branch out into their respective workshops.

The things for which economics, mathematics, statistics, operations research, computer science, and other fields have developed very intricate formal mechanisms will pop up mostly as pointers. The question which sorting, filtering, or separating algorithm to use is relevant and often decisive to the success of an economic activity, but it is secondary to the question when to sort, filter or separate — and what.

Instead it will take very close looks — some might think unreasonably close looks but my hope is the reasons for doing so will reveal themselves in due time — at existing economic artifices and their constituent parts. One of the motivations is to show that the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul and an online e-commerce platform have surprisingly many things in common, and there’s a reason for it.

An economic pattern language

To this end, EconPatterns — and I believe this is the defining novelty — will borrow liberally from design theory and practice, as well as from architecture. The chosen container for this endeavor is Christopher Alexander’s design pattern. There are many reasons for this choice, not the least of which is that design patterns have successfully been translated from architecture to software design.

The in-depth discussion of “why design patterns?” surely deserves its own article, but it also introduces an interesting tension. As design philosophies go, Alexander and the Bauhaus stalwarts are certainly at opposing ends of the spectrum, A to B, organic to geometric, habitable spaces to machines for living.

I’m hoping to put this tension to good use. Designing economic contraptions poses relevant questions beyond their productivity and efficiency. Which is a major reason why I am not trying to resolve that conflict or take sides.

Admittedly, the whole endeavor is open-ended, and the crucial question if the patterns sketched out so far will ultimately come together as a coherent whole is still unresolved. This is why the blog format is the right one at this juncture: to put the question out in the open while I present the first pieces of the puzzle.

EconPatterns will inevitably be shaped by my own background and my own particular interests, which is one reason why economic organization will be the initial focus. The fundamental model of the economy is different, as is the underlying concept of human behavior (as next week’s entry will show). I’m somewhat inclined to say that there are not that many people out there with a background both in design and economics, so I’m quite comfortable in claiming that the exercise should offer sufficient novelty.

I’m also very clear that I don’t hold exclusive rights to the very concept of design patterns — if anything I might be the first practitioner to apply them to economic design problems — but the ultimate defining characteristic of a design pattern that sets them apart from economic laws is that they’re entirely voluntary. They are simply proposals of how to look at, structure, and solve a certain design problem, and the ultimate arbiter for their success is if enough practitioners will find them useful enough to apply them to express their ideas.

Which in itself should hopefully take much of the pedantry out of economic debates.