How to Stay Locally Safe in a Global World

Cross-posted from Jade’s blog: parts 1, 2, 3

Introduction

Suppose your name is $x$ and you have a very important state machine $N_x : S_x \times \Sigma \to \mathcal{P}(S_x)$ that you cherish with all your heart. Because you love this state machine so much, you don’t want it to malfunction and you have a subset $P \subseteq S_x$ which you consider to be safe. If your state machine ever leaves this safe space you are in big trouble so you ask the following question. If you start in some subset $I \subseteq P$ will your state machine $N_x$ ever leave $P$? In math, you ask if

\[\mu (\blacksquare(-) \cup I) \subseteq P\]where $\mu$ is the least fixed point and $\blacksquare(-)$ indicates the next-time operator of the cherished state machine. What is the next-time operator?

Definition: For a function $N : X \times \Sigma \to \mathcal{P}(Y)$ there is a monotone function $\blacksquare_N : \mathcal{P}(X) \to \mathcal{P}(Y)$ given by

\[\blacksquare_N(A) = \bigcup_{a \in A} \bigcup_{s \in \Sigma} N(a,s)\]In layspeak the next-time operator sends a set of states the set of all possible successors of those states.

In a perfect world you could use these definitions to ensure safety using the formula

\[\mu (\blacksquare(-) \cup I) = \bigcup_{n=0}^{\infty} (\blacksquare ( - ) \cup I)^n\]or at least check safety up to an arbitrary time-step $n$ by computing this infinite union one step at a time.

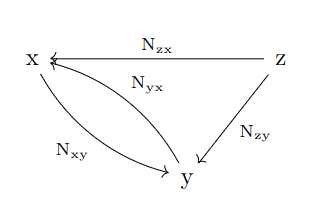

Unfortunately there is a big problem with this method! Your state machine does not exist in isolation. You have a friend whose name is $y$ with their own state machine $N_y : S_y \times \Sigma \to \mathcal{P} (S_y)$. $y$ has the personal freedom to run their state machine how they like but there are functions

\[N_{xy} : S_x \times \Sigma \to \mathcal{P}(S_y)\]and

\[N_{yx} : S_y \times \Sigma \to \mathcal{P}(S_x)\]which allow states of your friend’s machine to change the states of your own and vice-versa. Making matters worse, there is a whole graph $G$ whose vertices are your friends and whose edges indicate that the corresponding state machines may effect each other. How can you be expected to ensure safety under these conditions?

But don’t worry, category theory comes to the rescue. In the next sections I will:

- State my model of the world and the local-to-global safety problem for this model (Part II)

- Propose a solution to the local-to-global safety problem based on an enriched version of the Grothendieck construction (Part III)

Defining a World and Stating the Problem

Suppose we have a directed graph $G=(V(G),E(G))$ representing our world. The vertices of this graph are the different agents in our world and an edge represents a connection between these agents. The semantics of this graph will be the following:

Definition: Let $\mathsf{Mach}$ be the directed graph whose objects are sets and where there is an edge $e : X \to Y$ for every function

\[e : X \times \Sigma \to \mathcal{P}(Y)\]A world is a morphism of directed graphs $W : G \to \mathsf{Mach}$.

A world has a set $S_x$ for each vertex $x$ called the local state over $\mathbf{x}$ and for each edge $e :x \to y$ a function $W(e) : S_x \times \Sigma_e \to \mathcal{P}(S_y)$ representing the state machine connecting the local state over $x$ to the local state over $y$. Note that self edges are ordinary state machines from a local state to itself. An example world may be drawn as follows:

Definition: Given a world $W: G \to \mathsf{Mach}$, the total machine of $W$ is the state machine $\int W : \sum_{x \in V(G)} S_x \times \sum_{e \in E(G)} \Sigma_e \to \mathcal{P}( \sum_{x \in V(G)} S_x )$

given by

\[( (s,x),(\tau,d)) \mapsto \bigcup_{e: x \to y} F(e) (s, \tau)\]The notation $\int$ is used based on the belief that this is some version of the Grothendieck construction. Exactly which flavor will be left to future work. The transition function of this state machine comes from unioning the transition functions of all the state machines associated to edges originating in a vertex.

Definition: Given a world $W : G \to \mathsf{Mach}$, a vertex $x \in V(G)$, and subsets $I,P \subset S_x$, we say that $I$ is locally safe in a global context if

\[\mu (\blacksquare_{\int W} (-) \cup I) \subseteq P\]where $\blacksquare_{\int W}$ is the next-time operator of the state machine $\int W$.

The state machine $\int W$ may be large enough to make computing this least fixed point by brute force impractical. Therefore, we must leverage the compositional structure of $W$. We will see how to do this in the next post.

The Global Safety Poset

In this section we will give a compositional solution to the local safety problem in a global context in two steps:

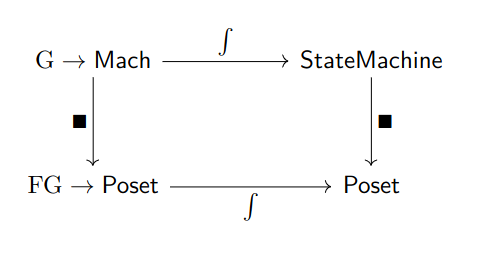

- First by turning the world into a functor $\hat{W} : FG \to \mathsf{Poset}$

- Then by gluing this functor into a single poset $\int \hat{W}$ whose inequalities solve the problem of interest.

First we define the functor.

Given a world $W : G \to \mathsf{Mach}$, there is a functor

\[\hat{W} : FG \to \mathsf{Poset}\]where

- $FG$ is the free category on the graph $G$,

- $\mathsf{Poset}$ is the category whose objects are posets and whose morphisms are monotone functions.

Functors from a free category are uniquely defined by their image on vertices and generating edges.

- For a vertex $x \in V(G)$, $\hat{W}(x) = \mathcal{P}(S_x)$,

- for an edge $e : x \to y$, we define $\hat{W}(e): \mathcal{P}(S_x) \to \mathcal{P}(S_y)$ by $A \mapsto \blacksquare_{W(e)}(A)$

Now for step two.

Given a functor $\hat{W} : FG \to \mathsf{Poset}$ defined from a world $W$, the global safety poset is a poset $\int \hat{W}$ where

- elements are pairs $(x \in V(G), A \subseteq S_x)$,

- $(x, A) \leq (y, B) \iff \bigwedge_{f: x \to y \in FG} \hat{W} (f) (A) \subseteq B$

Given a world $W : G \to \mathsf{Mach}$, a vertex $x \in V(G)$, and subsets $I,P \subseteq S_x$ then $I$ is locally safe in a global context if and only if there is an inequality $(x,I) \subseteq (x,P)$ in the global safety poset $\int \hat{W}$

My half-completed proof of this theorem involves a square of functors

Going from right and then down, the first functor uses a Grothendieck construction to turn a world into a total state machine and then turns that state machine into it’s global safety poset. Going down and then right follows the construction detailed in the last two sections. The commutativity of this diagram should verify correctness. I will explain all of this in more detail later. Thanks for tuning in today!