Optics for UI 1: Deconstructing React with Parametrised Lenses

Lenses model a new paradigm of programming based on bidirectional processses. Recently André Videla has figured out how use them to implement RESTful servers, and as we will see in this blog post, they can also capture UIs.

In this blog post we will look at UI frameworks like React and The Elm Architecture and see how to express them using parametrised lenses.

This is not the first time that lenses were applied to UIs, however there’s been a lot more work on understanding the category theory of lenses since then, especially parametrised lenses, and we will see how this new understanding gives us even more expressive power than before.

Bidirectional programming for component-based architectures follows a simple design pattern - information flows from parent to child components, and actions flow back from child to parent.

This is already different to how older top-down software architectures worked, but is in line with how modern React-based UI frameworks mediate between parent and child components.

Stateless components

In React terminology the signals flowing from parent to child are called “props”, and we can use callbacks to pass the response from a child to parent.

In addition to props, React components have a notion of internal state, which remains hidden from other components. The key idea is that rather than exposing the state itself, a component will only expose props derived from the state, which is what the child components will use in their logic.

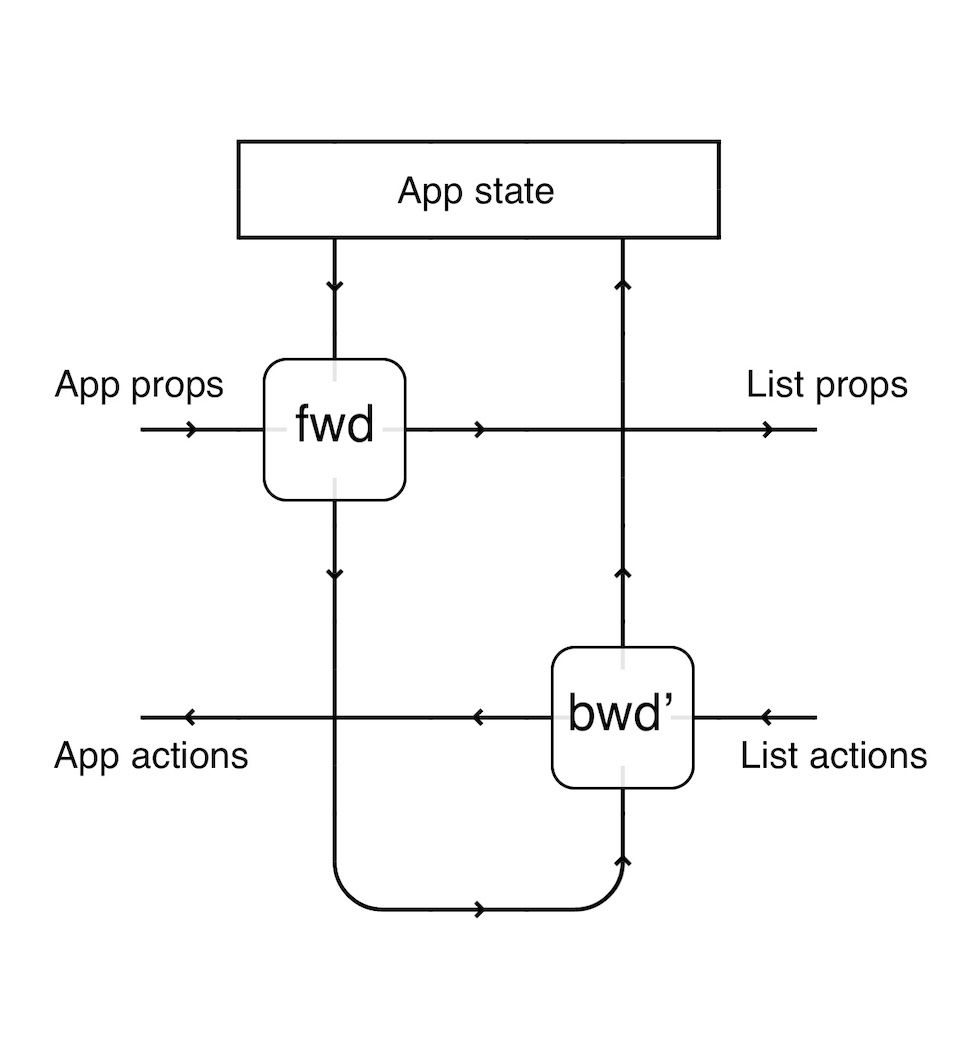

If we take a stateless view, our picture would look somewhat like this diagram of lenses:

$\binom{\displaystyle \text{WebApp props}}{\displaystyle \text{WebApp action}} \leftrightharpoons \binom{\displaystyle \text{List props}}{\displaystyle \text{List action}} \leftrightharpoons \binom{\displaystyle \text{List item props}}{\displaystyle \text{List item action}}$

Looking at it this way, we can see that this describes a bidirectional process. A web-app component will have access to the top-level prop, it will then pass a list to the list component, and the list component will pass each individual item to its own child component. Whenever an item is clicked, it will then pass on an action upwards up the hierarchy.

The forwards pass is determined by the flow of information from the parent prop, and the backwards pass is determined by the child responding to the parent.

The Elm Architecture

Of course in a functional world, with neither state nor effects, this becomes rather trivial. Props are immutable signals, so a child component can’t ask the parent to actually change a prop. We would either need to make the information contained in the props mutable, or add some kind of notion of effect.

Because this picture is rather limiting, languages like Elm take an entirely different approach and take state as primitive. A basic component in Elm would have a view function and an update function, and it’s not hard that the two form a lens:

view : Model -> Html Msg

update : Model -> Msg -> Model

In fact, because the update function takes a model to a model, we can see that this is actually a special kind of a lens, known as a Moore machine.

$\text{Moore} : \binom{\displaystyle \text{state}}{\displaystyle \text{state}} \leftrightharpoons \binom{\displaystyle \text{output}}{\displaystyle \text{input}}$

view : state -> output

update : state -> input -> state

Moore machines give you a lot of expressivity, but they also have a significant limitation - they don’t compose by lens composition. This means that if we have two separate components it’s easy to put them side-by-side using parallel composition, but there’s no way to talk about sub-components of a bigger component.

(Moore machines can compose with lenses to the left- and right- though, something we’ll talk about in a future blog post on reparametrisation).

Stateful components

So taking immutable props as primitive causes the framework to trivialise, and taking encapsulated state as primitive causes it to lose compositionality. Is there any way out?

Early experiments with optic-based UI frameworks tried to answer this question by weakening the requirement that state must remain encapsulated within a component. Instead, a parent components would expose parts of its state to its children, which would then be able to act on it.

This means that we would get a picture much like before, but now the state will be mutable.

$\binom{\displaystyle \text{WebApp state}}{\displaystyle \text{WebApp action}} \leftrightharpoons \binom{\displaystyle \text{List state}}{\displaystyle \text{List action}} \leftrightharpoons \binom{\displaystyle \text{List item state}}{\displaystyle \text{List item action}}$

The nice thing about this approach is that components can now be composed using lens composition.

Let’s say we have the following interfaces:

AppComponent = (AppState, AppUpdate)

ListComponent = (ListState, ListUpdate)

ItemComponent = (ItemState, ItemUpdate)

The key to translating from this into the language of lenses is to start by inverting the control. The component-based view takes components as primary and treats the information flow between them as implicit. What lenses do is to make this information flow into a first-class citizen. This is why instead we name the lenses and treat the components as implicit:

$\text{ListLens} : \text{AppComponent} \leftrightharpoons \text{ListComponent}$

$\text{ItemLens} : \text{ListComponent} \leftrightharpoons \text{ItemComponent}$

with the corresponding getters and setters

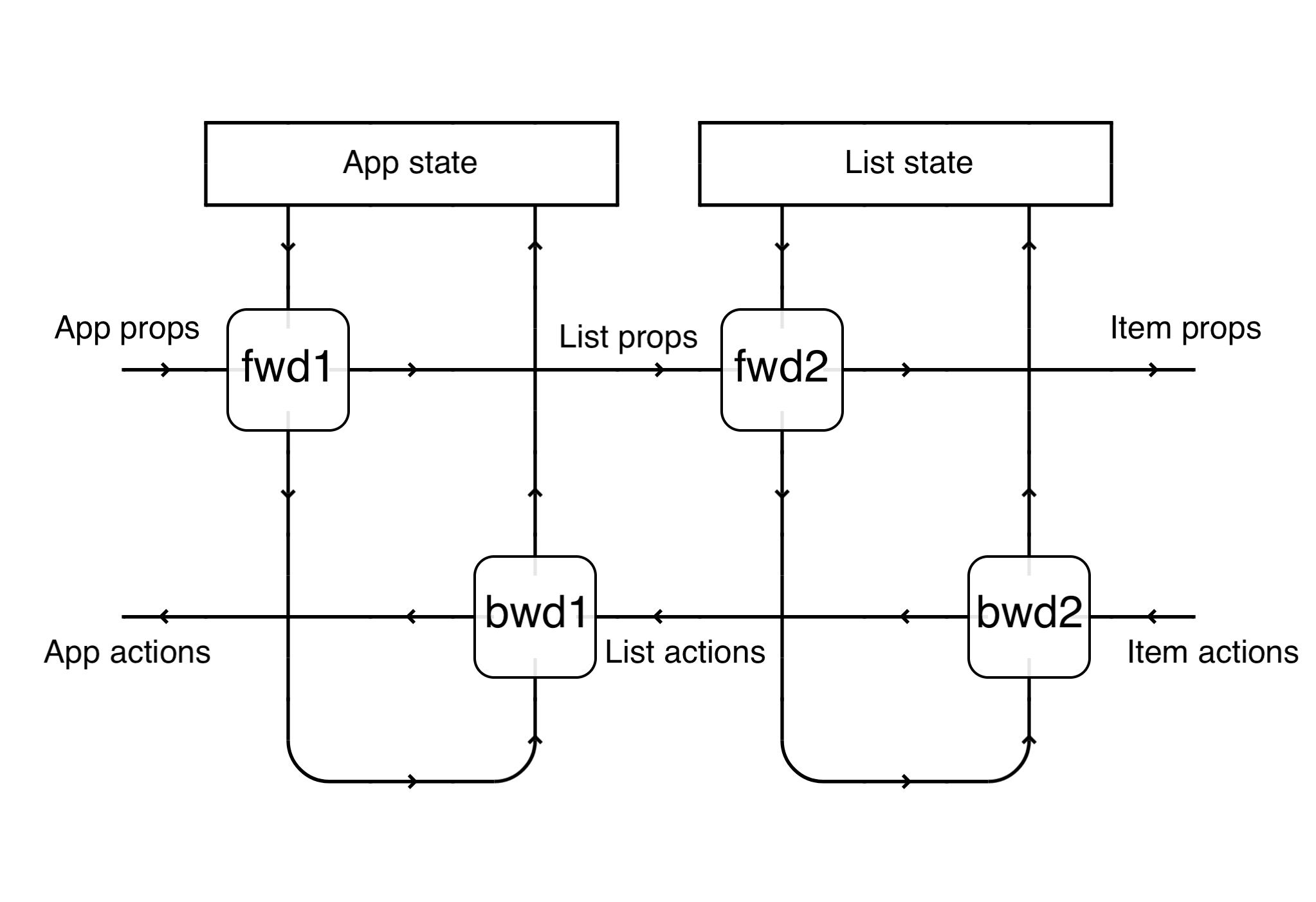

ListLens : Lens AppComponent ListComponent

fwd1 : AppState -> ListState

bwd1 : AppState -> ListUpdate -> AppUpdate

ItemLens : Lens ListComponent ItemComponent

fwd2 : ListState -> ItemState

bwd2 : ListState -> ItemUpdate -> ListUpdate

Their composition will give you the lens

ListLens . ItemLens : Lens AppComponent ItemComponent

In other words, knowing how to propagate information from one parent to a child, we get the propagation along a hierarchy.

Unlike the Elm model, this gives you hierarchical composition of components. But now we’ve lost one of the core principles of software development by exposing state across the entire application.

Is there a way to get the best of both worlds, to retain hierarchical composition of components while encapsulating state?

As we’ve seen so far, we want components to compose like lenses, but retain internal state. Is there a notion of “Lens with an internal state”? This is exactly what the Para construction does.

It turns out that there is, using the Para(Optic) construction that we’ve seen in a previous blog post. What’s more surprising, is that this construction gives you back exactly the React model.

React was right all along

How should state be organized? This is one of the fundamental questions of UI development. React takes this question further and asks “How should information flow within an application be structured?”

So far the models we’ve looked at have either worked with immutable props or mutable state. But what if we work with both?

React’s big insight was that a component has access to its own props and state, and the information it passes to its children is immutably derived from these:

fwd : (ParentProp, ParentState) -> ChildProp

On the other hand, when a component receives an update from a child, it now does two things: it can pass along a request to its own parent, or it can update its internal state.

bwd : (ParentProp, ParentState, ChildAction) -> GrandParentAction

update : (ParentProp, ParentState, ChildAction) -> ParentState

If we combine backwards and update into a single function,

bwd' : (ParentProp, ParentState, ChildAction) -> (GrandParentAction, ParentState)

we will see that this is exactly the same as the Para construction over lenses, which gives us the morphisms:

fwd : (a, p) -> b

bwd : (a, dp, db) -> (da, dp)

More importantly, composition of parametric lenses gives us composition of stateful components:

(These diagrams were made with Tangle).

Conclusion

We’ve looked at how we can use lenses to model several popular UI frameworks, as well as seen how the lens-based approach has evolved over the years. Our main takeaway is that lenses by themselves have always had something missing that kept them from being a truly powerful approach to UIs. And the claim that will be made in the subsequent posts in this series is that Para is exactly the structure that we’ve been missing. In the next few posts we will also see that Para is not only good for modelling state boundaries, but can be applied to modeling the boundaries of user input/output as well as async calls.